A few weeks ago while sitting with one of my friendly companion kea outside Aspiring Hut enjoying the balmy evening with a cuppa and many moths, a dark shadow appeared about a meter off the ground winging towards my face. We all three of us shared a mutual silence while I processed how come another kea could arrive in such a non typical silence.

At the last second it swooped upwards and landed on the guttering above me, again in total silence, by which time I decided it might be a young kea as it seemed smaller, however a little light forth-coming from my torch revealed otherwise ‘tho, and I found myself being stared unblinkingly at by the large yellow eyes of a ruru (morepork).

While processing this new development in my nightly meditation, another shadow silently winged past, and was soon joined by my new unruffled friend, both more interested in the moth hatch I realised. My kea looked on non plussed as I plumbed the darker depths of the nearby beech forest, hoping for another sighting, as in Maori mythology, ruru are considered to be wise and represent protection or a warning, and are linked with tapu (spiritual restriction), guardianship, forewarning, grief and awareness.

There is certainly something other-worldly about ruru, New Zealand’s native owl, and their mournful cry, echoed by its name, and grief as mentioned above was to follow!

They also have soft fringes on the ends of their feathers which makes them the original stealth predator, flying silently through the forest. They also have forward-facing eyes, giving them binocular vision – perfect for swooping on prey. While this maybe limiting as to surrounding views they can swivel their neck through almost 270 degrees…

…which was quite unsettling when a few weeks later I gently stalked and captured an injured one, in the same vicinity as the hut [thanks to Will Jarvis for the heads-up and assistance]. The deed was done by gently wrapping the bird in the darkness of a soft towel, through which I immediately felt it’s talons – something I’d forgotten to factor in. However thankfully they simply gripped my hands with the same gentleness.

A new journey then began as I transferred the patient into an appropriate cardboard box, and arranged transport [thanks Flo, for dropping all and driving up poste haste out of work hours on a Fri.] from the Dept. of Conservation in Wanaka , to a local vet.

During this time I think we developed a quiet bond as he settled, realising perhaps that safety was at hand. We made eye contact frequently, through various air holes in the box as he took quite an interest in transport arrangements. In between times he’d sit and rest, and through it all I thankfully could not detect any sense of shock or distress [see above header photo]. Just lots of curiosity…

The big yellow eyes were probably an inspiration to Maori carvers and in Maori haka and performances, and now I can see why. They’re compelling!

But sadly we were too late: The vet found the injury to the wing to be old and infected, and by the following evening despite antibiotics etc. my new ruru friend had passed on to the other realms alluded to above.

From various Fact Sheets on the Internet:

Stealthy fliers

Moreporks have soft fringes on the edge of their feathers, so they can fly almost silently and not alert potential prey. This also allows moreporks to hear the movements of their prey as they approach, rather than the noise of their own wings. They have acute hearing and their large eyes are very sensitive to light.

Able hunters

A morepork uses its sharp talons to catch or stun its prey, which it carries in its bill.

Breeding

Moreporks nest in tree hollows, in clumps of epiphytes (perching plants), or in cavities among rocks and roots. The female lays up to three white eggs, usually between October and November, which she incubates for 20 to 30 days. During this time she rarely hunts, and the male brings food to her. Once the chicks hatch she stays mainly on the nest until the young owls are fully feathered. They can fly at about 35 days.

Creator and Sponsor of this Site:

Donald from iCommunicate Wanaka is Seeking Employment Aligned with Environmental and Sustainability Values.

Communicating and tech-ing sustainably – because the future is too important to leave to typos and outdated systems

Unfortunately kea do not nest on slippery roofs!

Unfortunately kea do not nest on slippery roofs!

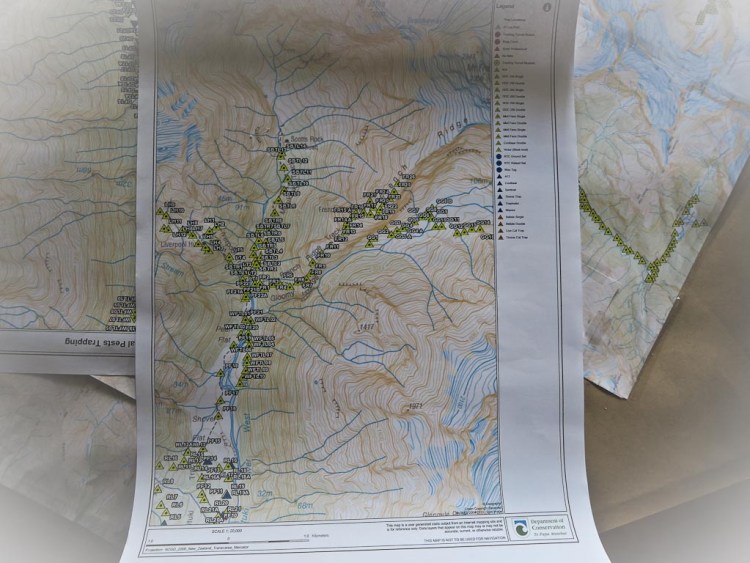

Traps of all types upstream from Aspiring Hut in the West Matukituki valley, Mt Aspiring National Park. Liverpool valley on the left, upper west Matuki. and Scott Bivy rock in the center, and French Ridge on the right.

Traps of all types upstream from Aspiring Hut in the West Matukituki valley, Mt Aspiring National Park. Liverpool valley on the left, upper west Matuki. and Scott Bivy rock in the center, and French Ridge on the right. A new kid on the block – one of many of the south island robin reintroduced some years back. Breeding has been so successful last spring that it’s hard estimate if we’re talking scores or hundreds of birds that have been bred by about 20.

A new kid on the block – one of many of the south island robin reintroduced some years back. Breeding has been so successful last spring that it’s hard estimate if we’re talking scores or hundreds of birds that have been bred by about 20.